|

The panda

has long been known in China. A dictionary, the Er Ya from

the Qin Dynasty, mentions the panda, known as mo, in about

220 BC, and during the Western Han dynasty (206 BC to 24 AD),

the emperor's garden in Xian is said to have housed a panda.

The grandson

of Tang Taicong, the first emperor of the Tang dynasty (618

to 907 AD) may have sent two live pandas to Japan as a token

of friendship, a gesture not repeated by China until the 1950s.

In spite

of this ancient knowledge and the panda's striking appearance,

the animal remained a creature of shadow rather than substance.

Chinese scrolls are crowded with tigers, cranes, turtles,

and others that have spiritual resonance in allegory, but

the panda is not among them. It seldom appeared in art until

the mid-twentieth century. Perhaps its fogbound mountain forests

were too remote and its

habits too elusive.

|

|

On 11

March 1869, a hunter brought a panda skin to the French Jesuit

missionary Armand David who realized that the "fameux

ours blanc et noir" was unknown to Western science. The

discovery sparked a controversy about whether the panda is

an "ours" (bear) or a member of the raccoon family.

The issue was not resolved until over 100 years later when

DNA analysis revealed the panda as an early branch of the

bear family. However, the panda itself retained its aura of

mystery.

On 13

April 1929, the Roosevelt brothers, Theodore and Kermit, were

the first foreigners to shoot a panda. During the next few

years, the acquisition of their trophy led to several other

hunts, sponsored by American museums.

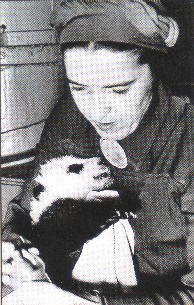

The event

that ultimately made the panda an icon of WWF and the conservation

movement, as well as helping to evoke universal

sympathy for the plight of the species, was the capture of

an infant panda by Ruth Harkness in 1936. When she brought

Su Lin, as it was named, to the United States, the animal

enchanted the nation, creating a panda

cult that survives still. It also led to an undisciplined

international scramble by zoos to exhibit pandas.

Between

1936 and 1946 a total of 14 pandas were taken from China by

foreigners during a period of political turmoil. Then the

country closed its doors to such exploitation. But within

a decade, China began to use

pandas as goodwill ambassadors, giving pairs to Russia, United

States, Mexico, Berlin and others, a total of 24 between 1957

and 1983. Yet the panda as a species in the wild remained

little known.

In the

mid-1970s a number of pandas starved in the northern part

of the animal's range after bamboo mass-flowered and died,

as it does periodically, only to sprout again from seeds.

A census at that time gave an estimate of about 1000 animals,

a figure certainly too low, but it alerted the government

to the panda's precarious position. Concerned about the survival

of a species considered to be a national treasure and whose

future was solely its responsibility, China initiated a panda

study in 1978. A field camp was built on a steep, forested

slope in the Wolong Reserve.

|

The

capture of an infant panda by Ruth Harkness in 1936 helped

to evoke universal sympathy for the plight of the species.

|